I Don't Like It Any More Than You Do

November 10, 2022

I don’t keep up much nowadays with what’s going on in space. I don’t watch SpaceX launches; I don't wonder about Mars, and I don’t marvel at the latest images from the big telescopes. I do watch Star Trek: The Next Generation sometimes, but the fact that the show takes place in space sometimes feels almost like an afterthought. Their advanced technology and supercomputers allow them to bypass many of the challenges inherent in human space travel. They don’t have a big rocket; they have some sort of ionic flux capacitor array. They don’t really talk about where they get their oxygen, and they don’t worry about food because they have replicators. Everything is taken for granted. It’s like living in a big futuristic house, but it’s also in space.

In the real world, things are a little different. As Isaac Brock explains in the song Cowboy Dan: “We need oxygen to breathe.” We need fuel and food and specialized torture machines that keep your muscles from atrophying. A modern space station resembles that passenger ship from 2001: A Space Odyssey; everything's built around Velcro. Velcro is one of the secret heroes of space travel. It solves many problems that emerge in space that aren't really problems on Earth. The use of Velcro, in a way, can act as a symbol for space travel as a whole: on Earth, it's a relatively simple and innocuous technology, mostly associated with children's sneakers; but in space, it's indispensable. There are plenty of little aspects of being in space that one must take into account before one leaves, aspects that are often mundane and sometimes don't seem that important.

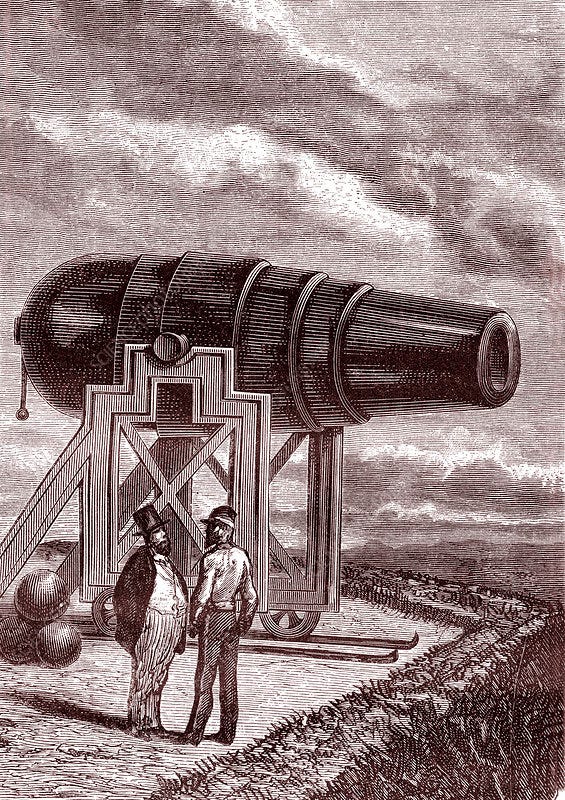

Jules Verne knew all about this. Jules Verne, I'll have you know, is a genius, and the key to his genius is his ability to write books about the most exciting subjects in the world and make sure that at least half the chapters are devoted to boring technical considerations. In From the Earth to the Moon, this genius is in full effect, as a significant portion of the plot concerns figuring out how to raise the necessary money; where to build the cannon; what type of materials to use; how to transport those materials to where the cannon is being built; the optimal circumference of the cannon and the length of the fuse; etc, etc. This is all certainly necessary, and interesting to a particular sort of person, but it's not exactly page-turning material. This is offset by the fact that every other chapter is as high-octane and intense as possible, including a late-chapter jungle duel that pops out of nowhere.

The general plot of the book is set off by the end of the American Civil War. The Baltimore Gun Club, a group of cannon and artillery aficionados who have been the pride of the nation for as long as their hobby was of the utmost use, is now in disrepair and rife with ennui. We join the Gun Club as they are commiserating their fallen hobby, lamenting the fact that the prospects for war in the near future are looking slim, and that there is no longer a steady rush of government cash available to fuel their escapades.

It's easy to see in these men the origins of what we now call the Military Industrial Complex, but it is also easy to compare them with other more sympathetic figures. I am personally reminded immediately of Jiro from The Wind Rises. He doesn't develop the Mitsubishi Zero because he wants to help Japan win the war; he does it because he loves airplanes, and he wants to make the best one: the most beautiful and graceful one, a plane that pushes forward humanity's long aviatory dream.

Jiro loves airplanes because he was once a child, and when he was a child, he wanted to fly. He was visited by an Italian man in a dream. You could imagine that some of these Baltimore Gun Club members may have been visited by, I don't know, Ottomans in their dreams. They love the smell of gunpowder, the roar of the explosion, and the beautiful parabola the ball makes as it sails through the air. (For more about love of rockets and the beauty of parabolas, see Gravity's Rainbow.)

The Baltimore Gun Club's president, Barbicane, understands that this technology they have developed must find a new use beyond killing, if their hobby is to survive at all. They will need to capture the public imagination somehow. He comes up with a scheme. The scheme is to fire a cannonball at the Moon.

It's important to note that it is not until almost halfway through the book that it is ever suggested that a man might ride this cannonball to the Moon. To Barbicane, the moon's importance is only as a giant moving target in the sky. He has no interest in furthering man's knowledge of the Moon; his interest is in furthering man's knowledge of artillery. Firing at the Moon is an interesting challenge for an artillerist.

The man who finally suggests to be allowed to ride on the cannonball is also not particularly interested in the Moon itself. He is an explorer who wants to visit the Moon because no one has gone there before. He wants to be the first. There's also the knowledge that he will almost certainly die. That's the sort of thing that thrills him.

When it comes to firing a cannonball, or a rocket, at the moon, there will always be a variety of motivations. In real life, during the Space Race, much of the funding was based on military considerations related to the Cold War. It would not be inaccurate to say that, from the side of the White House and the Defense Department, the concern was that whoever went to space first could drop bombs from there. If that's you, then you rule the world. If that's the other side, then your world is over.

However, that doesn't quite paint the whole picture. For every person who wants to rule the world, there's another person who just wants to build a spaceship. For every Soviet bureaucrat, there's a pilot with a death wish. For every White House ghoul, there's a guy who just wants to hold a piece of Moon rock in his hand.

When I was wandering through the Museum of Flight recently, I was overwhelmed by this dichotomy. For every commercial airliner, such as the Concorde or the Boeing 747, whose express purpose is transporting customers to exotic locations, there are three or four planes like the F-14 Tomcat, with informational plaques detailing their "heroic" actions during the Gulf of Sidra Incident; or the B-29 Bomber, the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb. Without even getting into the specifics of these conflicts, it does give on a bit of a sinking feeling, walking through the WWI and WWII exhibits and realizing that the simple technological joy of human flight has, since its earliest birth into reality (ignoring the impossible dreams of men like Da Vinci) been a means of throwing explosions at people.

There is a character in the video game Deadly Premonition named Wesley the Gunsmith. He sells the player weapons. Whenever you buy something from him, he says, "Guns are just tools for killing people. I don't like it any more than you do." This immediately raises the question: then why do you make and sell guns? The game doesn't let you ask that question, so I guess we'll never know.

My conjecture would be that he became fascinated by guns for some other reason than their ultimate purpose. Perhaps he encountered them early in life, and gained an appreciation for the way all the parts fit together, and the ways in which they can be customized. Eventually, this appreciation developed into a skill, a skill that was valuable to other hobbyists, as well as, of course, those who wish to use those guns for their original purpose, which is killing things.

Video game players, for the most part, like the tactile skill-feeling of aiming and firing projectiles at targets; however, most of them don't want to use real guns to kill people. Some of them do, but most of them don't.

The cynical view is that video games are a means of training kids to become soldiers. There are organizations out there who absolutely have that aim in mind. There are also video game developers who find value in the particular challenge of shooting games, and want to share that with people. These developers work for companies that want to use shooting games to make money, and these companies receive money from the organizations who want to train kids to become soldiers. So there's a lot going on there!

The cynical view is that airplanes are a tool for dropping bombs. You can look at that tweet about the US jet that shoots a billion missiles at once, and think about how that spray of missiles is going to decimate a city in the Middle East for no particular reason. You might then think, "Maybe we shouldn't have learned to fly at all."

The cynical view is that space travel was an extension of military preoccupations and military technology. The optimistic view is that space travel is a result of humanity's intrinsic scientific spirit of adventure and progress. Both of these views are true.

There is something about artillery that Barbicane loves. This something is divorced from the aim of murdering a bunch of people. With a little ingenuity, and a keen sense of the current social climate, he is able to re-orient the end use of cannons, from a “tool for killing people,” to a tool for firing stuff at the moon, all while maintaining the mathematical and logistical challenge that makes artillery so engaging to the members of the Gun Club. This is the sort of thinking that turned space travel from a militaristic race between competing world powers, to an endeavour that can result in the International Space Station, where a bunch of nations band together to facilitate moustachioed Canadians playing guitar in zero gravity.

It’s a beautiful thing.