I'm Not Good Enough

March 30, 2023

In 1995, Studio Ghibli released the first film directed by Yoshifumi Kondo. Three years later, he would pass away from an aneurysm, believed to have been caused by overwork, leaving Whisper of the Heart as his only full-length movie.

Whisper of the Heart was written by Hayao Miyazaki, famous for My Neighbour Totoro, Spirited Away, Kiki’s Delivery Service, among other animated classics. It is based on a manga by Aoi Hiiragi, which I have not read. It is likely that over the course of this review, I may attribute to Miyazaki and Kondo certain details that may be present in her work; I would like to apologize for that up front. This film is indebted to her work, and for that I must thank her.

Whisper of the Heart is a film about artistic creation. It presents in extremely sympathetic detail a pair of young artists, struggling to deal with the emotional turmoil that comes with growing into your particular craft.

The main character is a teenage girl named Shizuku. Shizuku is outgoing and social, although at times brash and unthinking toward others. She loves to read, and in the first part of the film she mentions several times her plan to read 20 books over the course of the summer break. She particularly loves fairy tales and imaginative stories — tales of heightened emotions and dramatic events.

These stand in stark contrast to the film's tendency to luxuriate in mundanity, its first scene being Shizuku walking home from a convenience store with a carton of milk. The first lines of dialogue are her mother asking why she got a whole plastic bag just for one carton of milk, to which Shizuku replies that they just give you one. It is in these first scenes that the tone of the movie is set: this will not be a movie that exaggerates; everything that happens from now on is real.

There are animated films just as imaginative and spectacular as Hayao Miyazaki’s, but there are none that manage as well as his to keep the characters and the world on our level, and make them so absolutely believable as human beings. Their characters are revealed through tiny facial expressions and gestures, and through casual lines of dialogue. This is most evident during the scenes that take place at Shizuku’s home. Every conversation naturally includes both plot-moving dialogue and everyday familial exchanges — “Do you want some coffee?” “Is your mother home yet?” “Have you seen my wallet?”

This naturalism is one of Miyazaki's superpowers, and this is why his films resonate so strongly with people. There is no greater example than Porco Rosso, where he makes a literal flying pig into a sympathetic man who you leave the movie sincerely believing is your friend.

While Whisper of the Heart does not travel to the heights of fancy that we see in Porco Rosso, Ponyo, or Spirited Away, the technique is equally effective in that it immediately convinces us to accept this world and all that may happen within it. This is vital for a writer of animated films, who has only around 80 to 120 minutes to tell a story that needs to go somewhere, and for that they will need in their arsenal a fair number of coincidences, chance meetings, and extraordinary events. For us to revel in these, rather than find them contrived or silly, we must view these events as the characters see them — by which I mean, we must view them in the same way we view the coincidences, chance meetings, and extraordinary events that occur in our own lives. Very rarely do we consider anything from our own experiences to be totally unreal, no matter how unlikely it is, because we are assured by all the everyday mundanity that surrounds us that our lives are, in fact, real and not some fantastical dream.

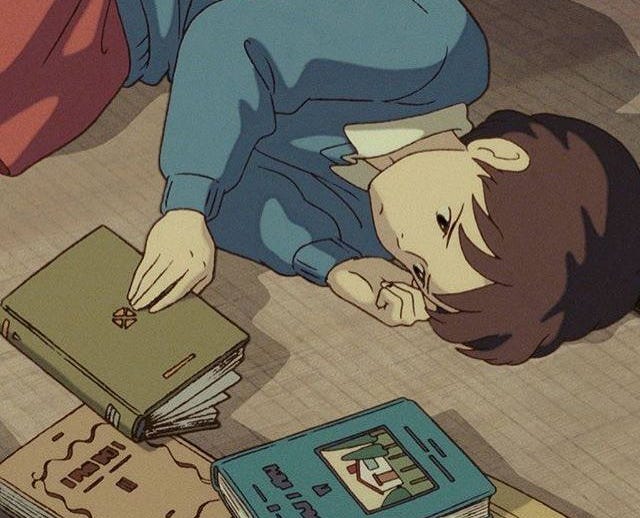

This skill is only accentuated by Kondo’s directing. The plot is carried forward at a brisk pace with the bare minimum of exposition, which allows us time to linger on silent scenes that give us a glimpse into the character’s inner lives: a young girl sliding off her desk chair to lie on the floor, or an old man nodding off before the fireplace.

This brings us to the movie's initial premise. Shizuku, in all the library books she has been taking out for the purpose of completing her goal, has found on their check-out card the same name: Seiji Amasawa. It seems that Seiji Amasawa enjoys all the same books she does, and has enjoyed them all only a few weeks or months prior to her own enjoyment. Her curiosity lies dormant until she discovers a book at her school's library donated by a Mr. Amasawa, and wonders at the relation. It turns out that Mr. Amasawa has a grandson who goes to Shizuku's school.

Meanwhile, Shizuku meets a boy. The first thing he does is criticize a song she is writing for a school presentation. She thinks he's a stupid jerk. Just like that, he's got her attention. For the next few days, he keeps popping into her mind at inopportune moments.

Later, Shizuku, on an errand to deliver a boxed lunch to her dad who works at the library, gets distracted by a cat riding the train. She wonders where the cat is going. When the cat decides to jump off at the same stop as her, she follows it. They wander past the library, up an alley, and into a part of town she had never been to before. Up there, she discovers an antique shop run by a kindly old man who shows her a grandfather clock he is repairing.

As we later find out, this old man is Seiji Amasawa’s grandfather, and the young man we saw acting like a stupid jerk is, in fact, Seiji Amasawa. He doesn’t actually read all the same books as Shizuku; he took them out in order to get her attention, just like he tried to get her attention earlier by insulting her. While the latter might not seem like an effective courting strategy, we have to remember that these are high-schoolers we’re talking about, and that they’re working with what they’ve got. Seiji’s tactics here are only slightly more sophisticated than those of the elementary school playground, but high school is that strange time of life when the elementary school playground intermingles with the adult world.

Seiji and Shizuku get to know each other, and we find out that Seiji has a passion for violin-making. According to an online dictionary, the term for this profession is “luthier,” but thankfully they never actually use this word in the movie. He just says he wants to be a violin-maker. His goal is to go to Italy in order to become an apprentice.

Shizuku is amazed by his commitment to this obscure craft, and his seriousness inspires her to take her own work more seriously. Besides being an avid reader, Shizuku is an aspiring writer, although she’s never actually written a complete story. We see her friends constantly referencing this aspiration, and at the beginning of the movie, she’s working on alternate lyrics for the song, “Take Me Home, Country Roads” for a class ceremony. However, she’s nervous and uncertain about sharing her work, even with her friends. She always downplays her writing before she lets anyone see it, trying to preempt any possible criticism.

While in her eyes Seiji is already more accomplished in his craft than she is, he has this same tendency toward self-criticism, and one of the movie’s most beautiful scenes is when he accompanies her on violin while she sings her new lyrics for him. At first, they are both clearly uncomfortable, but they push each other forward and by the end are entirely caught up in the music, especially when Seiji’s grandfather and friends show up and join in.

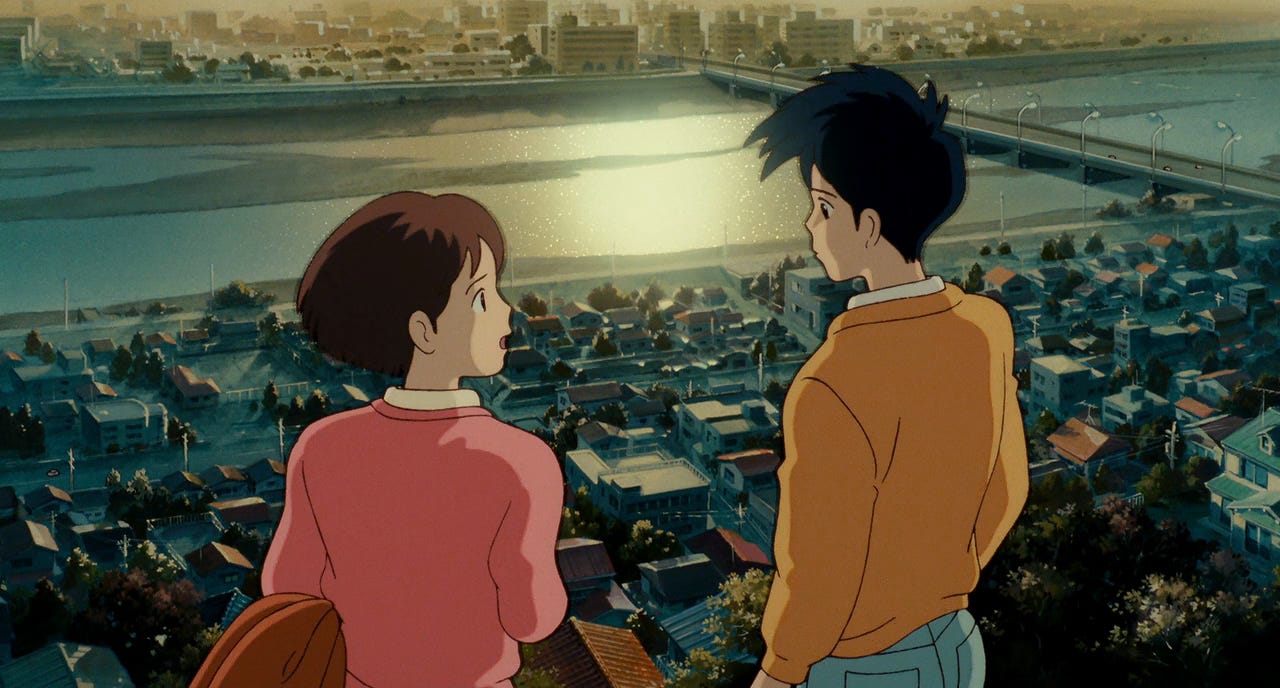

Shizuku and Seiji’s love story is full of understated moments like this. They’re a little awkward around each other, but it’s not exaggerated for comic effect, nor are their sentimental words underscored by bombastic musical swells. They fall in love slowly, one word at a time.

Soon after they meet, Seiji gets his chance to spend a few weeks in Italy trying out with a master luthier. In the meantime, Shizuku decides that she should test herself as well by working on a story. This whole time, she has felt inadequate compared to Seiji; no matter what anyone tells her, she feels that she’s not good enough, that her lack of accomplishment makes her a failure before she’s even started out.

At this point, things come to a head with Shizuku’s family. Her older sister is a university graduate who has come back to live at home while Shizuku’s mom works on her own graduate thesis. She is often frustrated by Shizuku’s childishness, pushing her to grow up and think seriously about her future, by which she means study hard at school in order to get into a good university. She considers Shizuku’s obsession with books to be mere escapism, a product of laziness.

Shizuku predictably responds to this pressure by lashing out in the opposite direction, declaring that she doesn’t even care if she finishes high school, and that she has other plans for her life. She’s fully committed to writing, and to testing herself with this first story, but she doesn’t have the confidence to admit this to her family. She tells them that she’s working on a “project” that’s important to her, but won’t let them know what it is.

When her parents receive her midterm report card and see that her grades have become dismal, they have a meeting in the kitchen. The scene is slow and tense, not with an aggressive sort of tension, but with the tension that forms between people who love each other but can’t communicate. Shizuku tells her parents that she needs to accomplish her goal, or she’s “not good enough.”

Her mother replies, “Not good enough for what? Why do you need to prove yourself?”

I will admit: every time I hear this line, I burst into uncontrollable tears. The question cuts so directly to the heart of the problem that is tearing Shizuku apart, and yet is entirely unanswerable. Shizuku's mother is right: she doesn’t need to prove herself to anyone. Her family, her friends at school, Seiji’s grandfather at the antique shop, and Seiji himself — they all believe in her, and love her for who she is. Yet she considers herself undeserving of this love, and feels that she needs to do something in order to justify this love, to justify her own existence — and not only do something but excel at that something, to meet this impossible standard she has set herself, and to meet it immediately, at sixteen years old, on her very first try.

What’s heartbreaking about this moment is that nobody can help Shizuku, because she has retreated so fully into herself. She will only accept judgements that match her harsh self-criticism, and she won’t accept any standard but the lofty one she has set for herself. People can tell her that her lyrics are great, or that she’s a good person, or that she doesn’t need to prove herself, but these words can’t reach her. Cut off from the world, she has no relief from the torment of her thoughts, reminding her every day that she’s not good enough, that she hasn’t done enough — that she needs to be better. Not that she needs to work harder or make progress toward her goal — that she needs to simply be better, now, and if it’s not now then it’s not good enough. It’s never good enough. Nothing will ever be good enough.

This kind of pressure is so excruciating because it’s impossible to explain or communicate. There’s no external entity you can point to. It’s not your parents, it’s not your teachers, it’s not the government, and it’s not society. It’s just this feeling that has risen up inside, gradually occupying more and more of your inner life. Were you to try to explain it, the most reasonable and empathetic response would be exactly what Shizuku’s mother says to her: Why? Why do you need to prove yourself? To which there is absolutely no answer.

Shizuku’s parents can’t help her, because she has too much pride or too much shame (or both) to ask them for help. Her father eventually sighs, and says to her, “Go ahead and do what your heart tells you. But it’s never easy when you do things differently from everyone else. If things don’t go well, you only have yourself to blame.”

What I appreciate about these lines is the combination of encouragement and realism. Shizuku is going to go her own way no matter what, but it’s likely that she doesn’t fully understand what this entails. By taking everything upon herself and not allowing anyone to help her, Shizuku is setting herself up for self-destruction. If she continues to act alone, any failure or stumble will bring her crashing down to the ground with no safety net. And at that point, it will be too late for anyone to help.

Thankfully, Shizuku does have someone to rely on. She asks Seiji’s grandfather for permission to base her story on one of the antiques in his store, and he allows her on one condition: that she must allow him to read the story when she’s done. This is Shizuku’s worst nightmare, but since it’s hard to say no to such a jolly old man, she accepts his condition.

This deal is not just an old man’s whim; Seiji’s grandfather sees exactly what’s going on with Shizuku, and understands that what she needs is someone to gently pull her out of her shell. His role is the patron saint of young artists. As mentor to both Seiji and Shizuku, his calming presence alleviates the ego-turmoil that tortures them as they take their first steps toward self-expression.

When Shizuku finally finishes her story, she brings it to Seiji’s grandfather and insists that he read it right away. She can’t bear to watch or even be in the same room as him when he reads, so she waits outside on the balcony. She’s on the verge of tears, her whole body numb with fear, tensed for rejection. For Shizuku, this story represents her entire self-worth; if it isn’t good, she is a failure. However, there is actually no “if” here. Shizuku knows the story isn’t good. She knows that she’s failed, and is prepared to treat any kind words from the old man as lies designed to make her feel better. And in fact, when he does come out and tell her that he enjoyed the story, she replies, “You have to tell me the truth. I know it’s a complete disaster.”

And yet, in another deep and secret part of her, she knows that her story is valuable. She knows that she’s put her heart into it, and that she’s tried her best. She’s passionate about writing because she likes it; she enjoys this indirect and faulty form of communicating her feelings. She won’t let this part of her out, and she won’t even acknowledge it within herself, but it’s there.

It’s not until Seiji’s grandfather explains that she should be proud of her hard work, that she allows herself to appreciate what she's done, and recognize the incongruity between the part of her that loves to write and the part of her that is constantly engaged in brutal self-criticism. Upon this recognition, she bursts into tears.

What Shizuku needed is for someone to tell her that she was on the right path, that there was hope for her. She needed someone to acknowledge that what she was trying to do is difficult, that it takes persistence, but that it is valuable in the end. It is by letting someone else into her story that Shizuku is able to find a balance where she can understand that she needs to improve, while allowing herself the time to actually do so. She had become so tied into knots fighting her lonely battle, that it didn’t even occur to her what she was doing to herself.

Not only this, she comes to realize that she’s not alone in her feelings. Seiji, who she thought was so accomplished and so ahead of her, is dealing with the exact same emotions. He pushes himself just as hard, and even though in her eyes he’s a masterful violin maker, in his own eyes, he’s not good enough.

The movie’s success lies in its deep and sympathetic understanding of young people, depicting them realistically and seriously. It does not treat chasing your dreams as a simple moral problem, but deals with the internal struggle that comes with actually making such an attempt. For many artists, it is not external conditions or pressures that hold them back, but their own fear and lack of confidence. Without support, they will collapse into themselves, allowing their negative emotions to seep into and corrode their ideas until all they can express is sorrow, fear, loneliness, and anger. A work that is solely the product of such bitter emotions can only ever tell half the story.

No other movie has touched me as deeply as Whisper of the Heart. I have experienced every aspect of Shizuku’s story, from beginning to end. I know what she’s feeling, even when she doesn’t say it — in fact, especially when she doesn’t say it. So much is communicated through her eyes, the slight flush of her cheeks, the movement of her hands. I know what it’s like to not be good enough, and to know that you will never be good enough.

When I wrote my first novel, I didn’t want to tell anyone I was doing it until I was done. I needed to prove myself. I needed to show everyone that I could accomplish something. But even after I was finished, even after I had allowed my friends and family to read it, I still couldn’t accept that I had done anything. I didn’t even want to call it a “novel,” because I felt it was too small, too insubstantial, and too stupid to deserve such a title. To call it a novel would be to acknowledge that I had succeeded in some way — that I had set out to do something, and actually done it. It would be to acknowledge that I was not a failure, and open up the possibility that I was good enough.

Six months after I allowed others to read the book, filing it away in the intervening time and refusing to look at it, I finally read the novel for the first time — not as the work that would “prove myself,” and not with the intent of picking it apart to show that I’m not good enough, but just as a book, a book into which I had devoted a great deal of time and effort. When I was finished, I cried, alone in my living room, those same tears that Shizuku cried on the balcony behind the antique shop. For the first time in a long time, I felt that I was good enough.