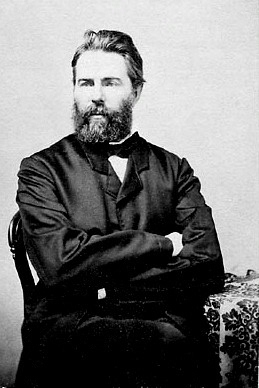

Herman Melville

1819-1891

Herman Melville’s output consists mainly of novels about the sea, from the youthful adventure Typee, based on his real experiences in the Pacific; to the more grandiose epic Moby-Dick. However, Melville had more in him than just maritime adventure, as he showed in his post-Moby-Dick career, which includes the bizarre Pierre, or the Ambiguities, the Kafkaesque Bartleby, the Scrivener, and the anachronistic epic poem Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land.

What carries through all these works is Melville’s characteristic charm, expressed via a mellifluous style and large amounts of wholehearted humour. At the same time, Melville’s good spirits are undercut by a prevailing cynicism toward mankind, as he cannot ignore the darkness and malignancy that lie behind our thoughts and actions. This combination is what defines Melville as an artist: a joyful, loud-talking sailor and a brooding, contemplative poet rolled into one.

Melville’s greatest works are easy to recommend, but his lesser-known works vary in quality and form, and are difficult to approach for the uninitiated. It’s quite easy to see why Moby-Dick and Bartleby, the Scrivener maintain a certain level of popularity, but its equally easy to see why everyone outside of strange individuals such as myself flee from more reckless experiments such as Pierre and Mardi. It is up to each reader to decide how deeply they wish to explore Melville’s unique oeuvre, but one would be remiss not to dip a toe or two.

My Top Five

- Moby-Dick (1851)

- Pierre, or the Ambiguities (1852)

- Typee (1846)

- Mardi (1849)

- Bartleby, the Scrivener (1853)

WORKS

Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846)

“Six months at sea! Yes, reader, as I live, six months out of sight of land; cruising after the sperm-whale beneath the scorching sun of the Line, and tossed on the billows of the wide-rolling Pacific — the sky above, the sea around, and nothing else![…] Oh, for a refreshing glimpse of one blade of grass — for a snuff at the fragrance of a handful of the loamy earth!””

As Ishmael later pines after the sea, Melville’s first work begins with a paean for land. On the very first page of his first novel, Melville manages to employ what would become his favourite word, verdure, setting the stage for a wonderful career.

In Typee, a young sailor absconds from his ship on an island in the Marquesas, driven to do so by a tyrannical captain (take note.) After clambering around in the jungle with his friend Toby, he finds a home among the Typee, rumoured to be the island’s most savage tribe. What he finds, however, is that Typee society is Edenic and idyllic when compared to the hustle-and-bustle of the civilized, Christianized Western world, and thus he settles in for an enjoyable few months among the cannibals. This only comes to an end when he starts to suspect that he himself might become an entree at an upcoming feast.

A riveting adventure story that calms into an anthropological account, all told in a sailorly way, emphasizing the exotic and always reaching for broad themes. The major aspects of Melville’s stylings are already present in this first work; the only things missing are the constant historical, philosophical, literary and mythological allusions that play such a major role in Moby-Dick. What we are left with, then, is perhaps a more direct look at Melville as an individual, before he ever thinks of himself as an “artist.”

Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847)

Following directly from Typee, Omoo follows a similar tack but this time among the inhabitants of Tahiti. Unlike the Typee, the Tahitians have more intricate connections to the Western powers in the area, much to their detriment. Omoo is a comic adventure, less focussed than Typee but perhaps more fun. You would do well to think of the two as a set, whose major theme is the relationship between European Christendom and the native inhabitants of the Polynesian islands.

Mardi: and a Voyage Thither (1849)

After both Typee and Omoo, both based on Melville’s real-life experiences, were maligned as fantastical untruths, Melville decided to throw caution to the wind and write a truly fantastical untruth.

The result is a 700-page collage of allegory and imagination, seeming to contain almost every idea that had ever popped into Melville’s head. Melville (disguised as a deity), accompanied by a demigod King, a historian, a philosopher, and a poet, explores a series of islands full of silly gimmicks and contemporary satire, all while discoursing about the nature of just about everything. The historian, philosopher, and poet all represent aspects of Melville’s literary personality, with the King serving as a means to put an end to their incessant conversations and keep the story moving.

But while the story always moves, it never quite goes anywhere; after almost 200 chapters, the novel comes to an abrupt end, confirming its status as not really a novel at all. Mardi is perhaps Melville in his purest form, not constrained by any particular form but simply unleashed on the page in an extended fit of whimsy.

Redburn: His First Voyage (1849)

Both Redburn and White-Jacket were written in a mad rush after the failure of Mardi: not the sort of inspired mad rush that led to Moby-Dick, but a rather prosaic and business-like mad rush that led to one decent and one relatively mediocre sailing novel.

Redburn certainly has its moments, most of which take place on land, as Redburn explores England in a vein reminiscent of Melville’s own transatlantic experiences. Here, Redburn encounters the poor and the rich sides of this frightful world of ours. At sea, Redburn is introduced to life as the greenest of sailors, and meets a few characters reminiscent of Melville’s later, more famous personages.

White-Jacket; or, the World in a Man-of-War (1850)

I regret to say that this novel is fairly forgettable. There are glimpses of that Melville magic, but not in any potent, focused way. This time, we are on a man-of-war, which gives Melville an all new set of maritime activities to describe. Emphasis is placed on the dishonorable act of flogging as punishment, which Melville seemed to have a personal vendetta against (which is honestly fair enough.) Overall, not much to write home about, although I know people who will defend it vigorously. I will leave it to them to do so, instead of pretending at a passion which isn’t mine.

Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851)

Melville’s masterpiece, and possibly the greatest novel ever written.

The grand joke of Moby-Dick is that the Pequod is filled with people who have some sort of overwhelming passion for whaling — from Ishmael, who loves the species to a comical degree; to Ahab, who has developed an all-consuming enmity for one particular whale — when, in real life, whaling was the least-glamorous of all boat-based professions, and most people aboard a whaling boat were not there by choice. The story transforms from a comic-philosophical adventure — starring one of the funniest fish-out-of-water protagonists in fiction — to a Shakespearean tragedy so gradually that you can’t even pinpoint exactly when it happens. In all, a frankly bizarre novel that seems to exist in spite of itself; an entity wholly unique to this world that will never be replicated or surpassed.

Further reading: Call Him Ishmael

Pierre; or, The Ambiguities (1852)

A truly bizarre follow-up to Moby-Dick that manages to one-up all its myriad absurdities. Pierre is a scion of an aristocratic American family with a strange relationship to his mother, and an even stranger relationship to a girl who may or may not be his long-lost sister. Featuring dramatic twists that emerge from nowhere, important backstory that reveals itself midway through and drastically alters the course of the novel, and emotional outbursts that seem to come more from Melville himself than any of the characters involved, this is a book that refuses to conform to any standard one would wish to place upon a novel.

The style is Melville at his most grandiloquent, clearly having the time of his life as he fails in every conceivable way to construct an appealing, readable story. And it is because of all of this that I love Pierre, deeply and with great passion, in a way I could never love a novel that gets it all right.

Further reading: A Brief Introduction: Pierre, or The Ambiguities by Herman Melville

Isle of the Cross (1853) (unpublished and lost)

Being entirely lost to time, we must assume that this is Melville’s greatest work.

Bartleby, the Scrivener (1853)

A strange new employee enters the law offices of our fastidious narrator: Bartleby, a quiet young man who at first seems to have a driving passion for copying. However, when our narrator requests some help proofreading a document, he receives, for the first time, Bartleby’s enigmatic refrain: “I would prefer not to.” What follows is a hilarious tale of radical noncompliance which I have to constantly remind myself wasn’t instead written by Franz Kafka.

Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (1855)

An adaptation of a civil war biography. Melville breathes a little life into it, but only enough to liven up a few brief moments; the rest is fairly dull.

The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade (1857)

Melville’s final novel, and the end of his “literary career.” A departure from his most significant works, in that it takes a broader perspective, following a whole collection of characters aboard a river ferry. The theme of their encounters is mutual trust and distrust, as these strangers engage in benign conversation, business dealings, and such day-to-day transactions as a simple haircut. All of these are described with Melville’s characteristic humour as well as his countervailing cynicism, which gives the novel its ambiguity and sharpness. Its rare to see a theme explored with such clarity and acuity, and shows the breadth of Melville’s talents, had he allowed himself to fully explore them.

Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land (1876)

According to something I read, this is the longest epic poem ever published in English. It’s a valiant effort, but as you might expect, the verse is fairly inconsistent and rarely reaches a truly poetic register; it mostly reads like prose that’s been translated into rhyming iambic tetrameter.

The story tells of a young American Protestant and a few companions as they travel across the Holy Land, meeting strangers along the way. His travels are precipitated by him falling for a Jewish girl who then becomes ill, and one of the themes of the poem is Clarel’s growing doubt regarding the efficacy of sticking to a single, firm religion. The poem is at its best when throwing its characters together, but the whole thing is honestly a little let down by the constraints of the form. I hugely respect Melville for taking such a wild swing, but the final result is unfortunately quite uneven.

UNREAD

- The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles (1854)

- Benito Cereno (1855)

- Battle-Pieces and Aspects of War (1866) (poetry)

- John Marr and Other Sailors (1888) (poetry)

- Timeleon (1891) (poetry)

- Billy Budd, Sailor (An Inside Narrative) (1891; unfinished)